Introduction

For thousands of years, Order Books have played a fundamental role in the world of trade, diligently recording transactions, and providing an organized account of market activities. The emergence of DeFi in recent years saw an application of this age-old model untethered from centralized authorities or intermediaries. Ultimately, the underlying technology wasn’t ready and liquidity issues pushed the space towards a fresh innovation - AMMs.

Today, most DEX protocols operate with passive liquidity provision and explicit AMM pricing curves. While this approach works well for longer-tail assets with lower liquidity levels, pricing fat-tail assets like BTC and ETH is inefficient.

Historically, the sheer magnitude of on-chain transactions and the computational resources required for a Central Limit Order Book (CLOB) made its implementation prohibitively expensive. However, recent developments in L2 tech and new, powerful Layer 1 solutions will drive down the cost of blockspace.

Order Books may finally emerge as a viable option across ecosystems and attract sophisticated traders and market makers on-chain.

In this article, I will explore the historical context and rationale behind AMMs, their ultimate inferiority compared to Order Books and the path towards a cross-chain Order Book that could revolutionize the world of DeFi once again.

If you are already familiar with AMMs and their drawbacks, feel free to skip to Order Books - a better solution. Let’s get started.

A History Lesson

Market Makers have emerged out of a necessity for higher market efficiency. A sell and a buy order rarely line up by themselves. An external force is needed to facilitate quick and efficient order flow.

In the early days of modern financial exchanges, this role was filled by individuals aiming to profit from the bid-ask spread while carefully hedging risks. Over time, the once manual task was pushed towards automation and today, market makers enhance liquidity in diverse markets, spanning equities, foreign exchange rates, and tangible assets.

One might think that the emerging DeFi sector has also adopted this highly efficient model used in legacy markets. Well, it tried to at first with protocols like EtherDelta but the nature of the underlying blockchain prevented efficient market-making from taking place. You see, to react to volatility, MMs need to quickly add and remove orders, often multiple times within a minute. Gas fees made this impossible.

The lack of efficient market-making meant that spreads were often 10% or even higher on critical pairs. If on-chain markets were to facilitate significant volume, another model had to be used. The space had to move away from the old and proven “Order Book”.

In a 2016 Reddit Post, Vitalik Buterin discussed the idea of running on-chain exchanges the way prediction markets are run. Over the following years, this idea picked up steam and in 2018, he followed up with another article further fleshing out the approach. A couple of months later, Uniswap launched, popularizing the first generation of AMMs.

AMMs - a (not so technical) Overview

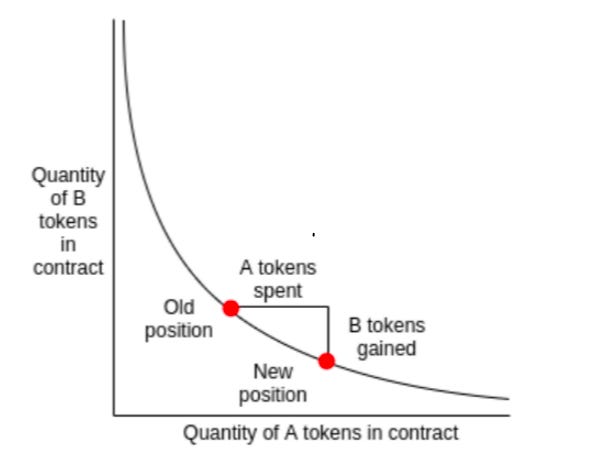

So what are these automated market makers? In essence, they combine the two (or more) assets being traded into one liquidity pool. The AMM can then quote a price according to a simple pricing algorithm that takes into account the ratio of assets in the pool. Uniswap v2 f.e. introduced the constant product equation x * y = k that prices over 2100 token pairs today. This article does a great job illustrating the concept with clear examples.

For the first time, a decentralized exchange could enable larger trades between assets without relying on intermediaries. The central role of market makers has faded into the background as the emphasis shifted towards passive liquidity provision.

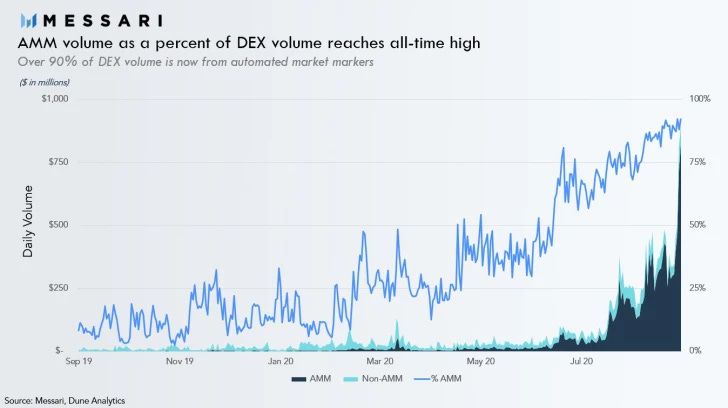

Looking at on-chain volume and TVL shows the massive impact this innovation had on the DeFi sector. During the bull market, the AMM model has proven superiority over other mechanisms. It has remained in this dominant position until today.

AMMs have brought reliable and permissionless trading to the world while creating opportunities for yield-seeking market participants. Given their proven potential, why haven’t we seen AMM adoption reach traditional financial markets?

AMMs - Drawbacks

Despite their achievements, AMMs have a set of inherent drawbacks that affect various parties involved; Liquidity Providers, Protocols and Users. Some of them have been addressed by employing complex mathematical formulas while others are simply impossible to fix. One of the most widely recognized issues associated with AMMs is Impermanent Loss (or Divergence Loss).

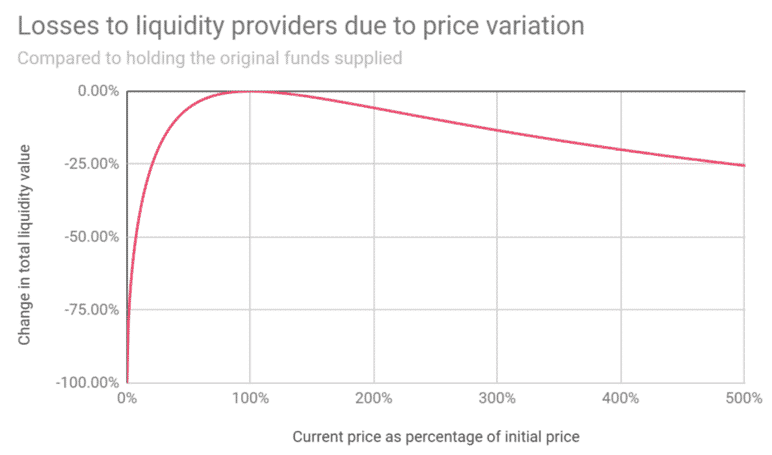

The concept describes the idea that providing liquidity often yields lower returns compared to holding the assets directly. As asset prices diverge, the AMM consistently purchases the underperforming asset while selling the outperforming one. The graph below illustrates this.

In other words, liquidity providers are basically guaranteed to underperform in an environment with any degree of volatility. Logically, LPs have to be compensated in another form, namely through fees.

Within every ecosystem, only a select few critical pools manage to maintain volumes substantial enough to draw in LPs consistently. Smaller, long-tail pools require external incentives to acquire sufficient liquidity. The most common approach to accomplish this is liquidity farming, the emission of tokens to pay for mercenary liquidity. This underscores the second notable drawback - Unsustainability.

Emitting tokens to incentivize liquidity is a common procedure. It started with food farms in the early days of DeFi Summer and persisted throughout the bull market. However, as the bear market set in, questions arose about its sustainability. After all, what is the worth of a token that inflates continuously and is sold off by mercenary farmers?

Zero. At least after a while. As tokens are sold off, prices decrease, especially in a bear with no inflow of exogenous capital. To continue attracting liquidity, emissions then have to increase. You’re stuck in a negative feedback loop.

So far I’ve looked at how AMMs are subpar at generating yield for LPs and promote unsustainable token emissions for protocols. In a third step, let’s look at them through the eyes of users.

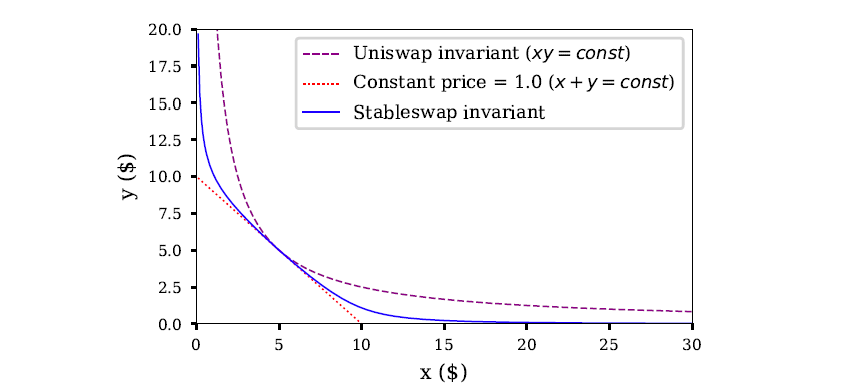

Users care about swapping at fair and predictable rates. They expect trades of any size to execute at close to the market rate. However, CPAMMs (the ones with the x*y=k curve) aren’t particularly good at that as they introduce substantial Price Impact. This issue can be mitigated by employing more intricate pricing curves designed to maximize capital efficiency near the equilibrium (like Curve’s Stableswap invariant).

Simply put, using an almost linear pricing curve increases capital efficiency.

However, such curves are only applicable to correlated assets like stETH/ETH or USDC/USDT that don’t diverge a lot. Prices start to move exponentially towards the outer bounds as you can see in the graph above.

To offer increased capital efficiency for uncorrelated assets, UniV3 and CurveV2 introduced concentrated liquidity (one manually, the other automated). In Uniswap’s case, this gave LPs granular control over what price ranges their capital is allocated to. LPing started to become a more active task, as liquidity had to be manually set around the current market price. Sound familiar?

In other terms, UniV3 is Uniswap’s way of approximating something close to an Order Book. In reality, we already have something that works better.

Actual Order Books.

Order Books - a better solution

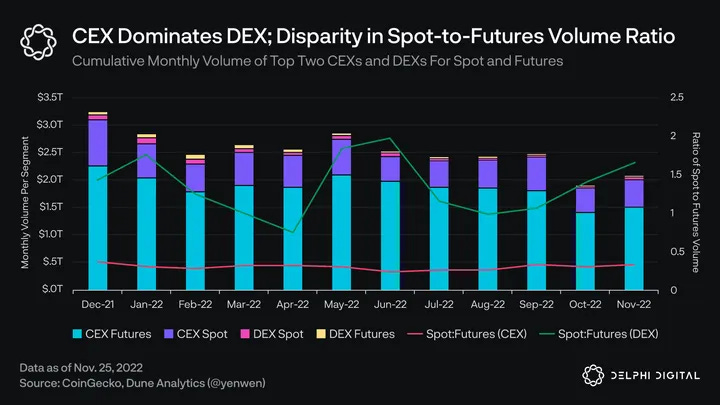

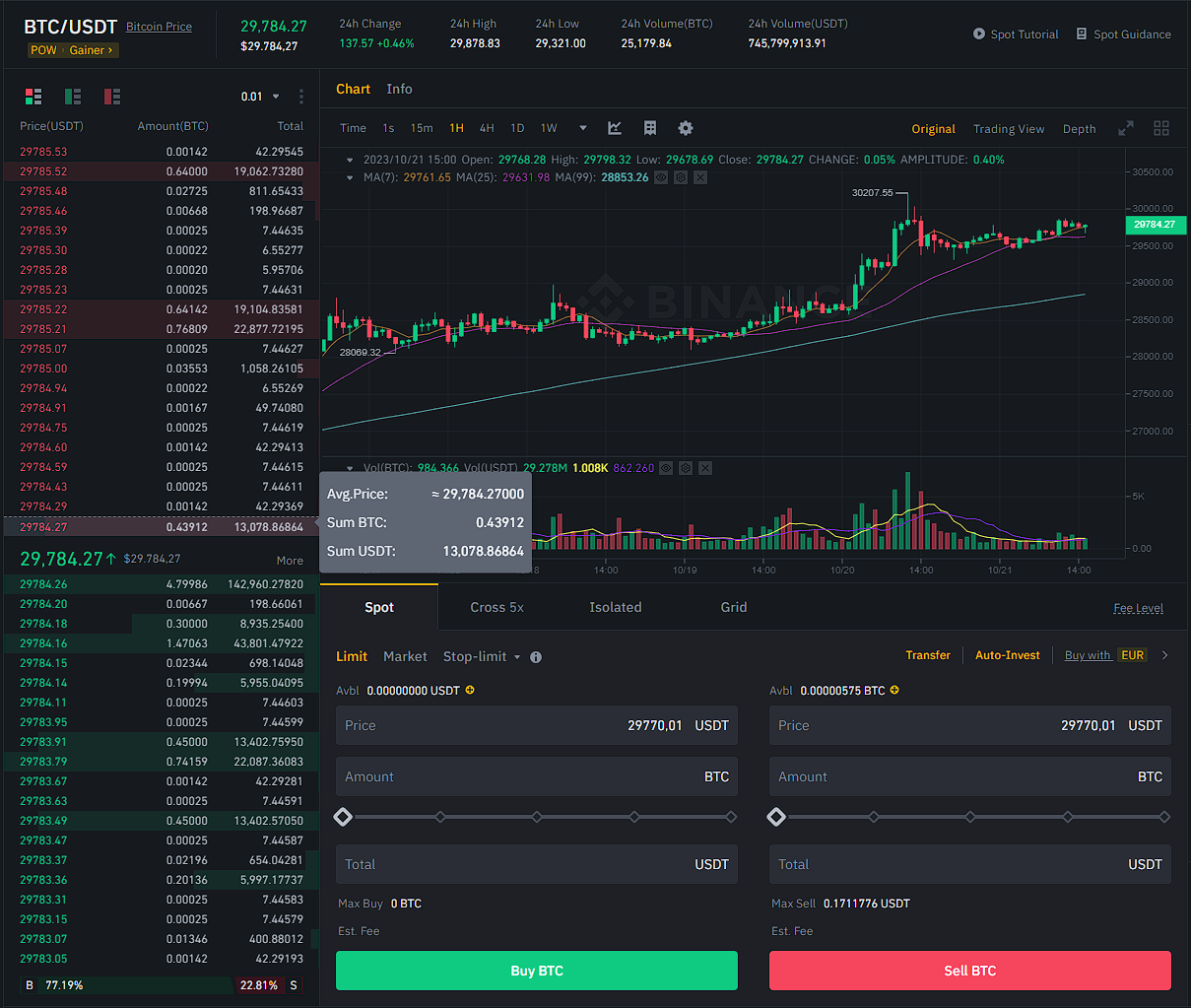

AMMs have had a significant impact on DeFi, however on-chain volumes pale when compared to those of centralized exchanges. CEXs have maintained their dominance, even in the aftermath of events like Mt. Gox and FTX. A loss of trust in centralized platforms and crypto’s underlying ethos might drive some users towards self-custody. Yet, the massive difference in UX between DEXs and CEXs prevents a fundamental transition.

Sophisticated traders, market makers and institutions won’t bring their trillion-dollar volumes to an inefficient AMM with pre-determined pricing curves that can’t accommodate their highly specific needs.

DEXs must offer a comparable experience to centralized exchanges to compete at scale. - Sam Xiao

The logical next step is to migrate Order Books on-chain. However, as previously mentioned, this task is more complex than it may seem. To grasp the intricacies involved, let’s talk about what Order Books actually are.

An Order Book is essentially a database that aggregates and lists orders. Incoming orders can take many forms, including limit, market, and stop orders and once submitted, they are stored according to price level and time of submission. When a newly submitted order aligns with an existing one, a trade is executed. Simple enough.

Their nature provides traders with a clear view of the current market’s supply and demand dynamics, offering essential data points such as real-time prices, bid-ask spreads, and more. This transparency helps them to make informed decisions and assess the liquidity of a particular instrument.

Another important aspect of an Order Book is its ability to handle large trading volumes efficiently. In a highly liquid market with significant makers and takers, the matching engine can quickly and efficiently match and fulfil orders.

The main challenge in creating a fully decentralized, on-chain Order Book revolves around replicating the efficiency of this matching engine. In a decentralized protocol, there is no place for a centralized entity tasked with order matching and trade settlement like on CEXs. Traders submit orders through smart contracts, and the Order Book is maintained on a blockchain.

Historically, the feasibility of such systems has been constrained by the speed and throughput limitations of blockchains, as well as the significant gas costs involved. After all, the task of aggregating, organizing, and listing hundreds of orders every minute is computationally demanding and resource-intensive.

Order Books Today

Right now, there are multiple DEXs leveraging CLOBs (Central Limit Order Books), and they typically fall into one of two categories:

(a) Purpose-built L1 DEX with some centralized features

These can directly compete with CEXs in terms of speed, efficiency and liquidity. While they operate on a blockchain, their infrastructure retains some centralized elements to achieve high speeds. Examples are dYdX with a daily volume of around $1b and the newer, smaller Hyperliquid.

(b) Fully on-chain, permissionless DEXs that operate on a fast and cheap blockchain

In this category, Solana is a prevalent choice due to its high throughput and low transaction costs, making it an appealing platform for running a decentralized Order Book. Some prominent examples include the Serum Fork Openbook and Phoenix, both of which can be accessed through Jupiter.

I believe that the second category will continue to grow in the near future. This expansion will be driven by the emergence of more cost-effective blockspace on L2s, ongoing innovation in the field and the expected rise in on-chain trading volume. Notably, the introduction of Proto-Danksharding through EIP-4844 will accelerate this narrative.

As Order Books gain market share at the expense of AMMs and an increasing number of both Layer 1 and Layer 2 solutions become capable of supporting such DEXs, we may need to consider yet another paradigm shift: Cross-Chain Order Books

Cross-Chain Order Book

Liquidity Fragmentation has been a persistent issue within the DeFi space on multiple levels. Within a single ecosystem, there are often multiple AMMs with liquidity pairs that overlap. Aggregators offer users a way to find the most efficient trading route. By splitting up trades and using multiple different DEXs, returns can be maximized.

Extending this aggregation philosophy to a cross-chain context can also improve execution. Here, intermediaries like interoperability protocols and bridges are required to enable asset flow between chains. In combination with chain-agnostic liquidity pools cross-chain DEXs can be created.

Now imagine that instead of being confined to one isolated liquidity pool, you could instead tap into the market’s total liquidity. Cross-chain Order Books make this possible by using Intents and Asynchronous Execution. Let me explain.

How Cross-Chain Order Books Work

Let’s say a User wants to swap USDC for the maximum amount of ATOM. Traditionally, they would have to find the best pool, fund a new wallet, move to Cosmos, execute the trade and move back. Each of these steps introduces UX challenges and causes delays in execution. However, through a cross-chain order book, the user can simply post their intent and wait for someone else to execute it.

Intent - users specify the end state they want and abstract away bad UX to more sophisticated parties.

Once an intent hits the Order Book, market makers start to compete for its execution. Assuming the price is adequate, the intent is executed asynchronously by the quickest market maker. It’s important to note that the market maker doesn’t immediately carry out the trade; instead, they satisfy the intent and postpone execution (in other words, execute asynchronously). Let’s visualize this with our previous example.

The user sends USDC and receives ATOM on the destination chain. Assuming the market maker held ATOM on the destination chain, no actual trade ever happened. Instead, the market maker ends up with less ATOM and some USDC on a different chain. To rebalance the portfolio, they will find the most efficient route and time to swap from USDC to ATOM. Et voila, the user has offloaded execution to the market maker.

The original article continues with a presentation of the deBridge protocol and their cross-chain order book. However I won’t feature that here. Why would I. The product is great but the article stands on its own.

May the best order book win. Cheers.